Dazzling – the Portsmouth man who went to war with paint box and palette – Nostalgia

H-HOUR minus one.

Cold dawn breaks on June 6, 1944, a day of destiny for thousands of men crouching in wave-tossed landing craft as the vast armada closes on its objective.

Suddenly, as the mighty fleet ranges on the Normandy coast, all hell breaks loose.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmid the turmoil, the flashes and roar of thousands of guns, shouted orders and crump of exploding shells, a man stands apart on the bridge of the destroyer HMS Jervis, oblivious to the mayhem of battle.

Striving to keep his balance on the plunging deck, Portsmouth-trained marine artist Norman Wilkinson calmly pulls out a Windsor & Newton sketch pad and rapidly records the panoramic scene as conflict rages from horizon to horizon.

At lightning speed, he fills page after page with his pencil...

At the top page he scribbles: ‘06.24. Sun catching small cloud.’

On the next page: ‘06.25 – opened fire.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExactly what Norman Wilkinson CBE saw from Jervis’s cramped bridge in the next 60 minutes before H-Hour off Port en Bessin, was revealed at HMS Dryad, Southwick, where Allied Supreme Commander General Eisenhower and naval operations C-in-C Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey had their HQ.

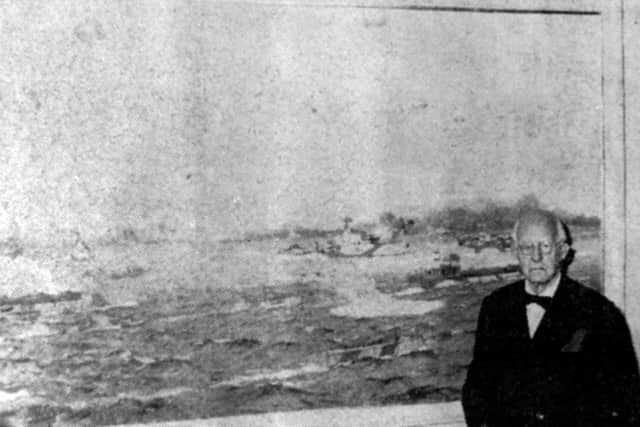

I met the 86-year-old, whose imagination skills were forged at Southsea School of Art in the late 19th century, in May 1965 when he went to Southwick House for the unveiling of his 10ft x 5ft oil painting of D-Day – the result of his ordeal under fire.

He presented the picture, showing Jervis’s 4.7in guns blazing, with his original sketches to the wardroom of the former Royal Navy Navigation School and it was mounted opposite the famous wall map depicting the landings at H-Hour.

He told me he only made it to Normandy as a ‘semi-stowaway’ after being invited on board by a friend; when the captain heard about it, he was ordered off the ship, but then invited to stay for a drink.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘I didn’t obey the order and spent the next couple of weeks wandering around in helmet and flash gear,’ he said.

The presentation was an honour for Dryad because collections of Wilkinson’s paintings normally hang in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich and numerous other top art galleries.

But his name had already been made 28 years earlier during the First World War with a revolutionary visual art form, involving precision daubing on a massive scale.

While serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve he’d been assigned to submarine patrols in the Dardanelles after witnessing the aftermath of the abortive Gallipoli campaign.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack home in 1917, he was sent on minesweeping patrols at the time when German U-Boats were torpedoing and sinking up to eight British ships a day.

‘I suppose it came to me in a flash of inspiration,’ he recalled. ‘I realised it was impossible to disguise a ship at sea, but it might be possible to confuse U-Boat captains aiming at a distance from periscopes just above the surface as to their targets’ course and heading.’

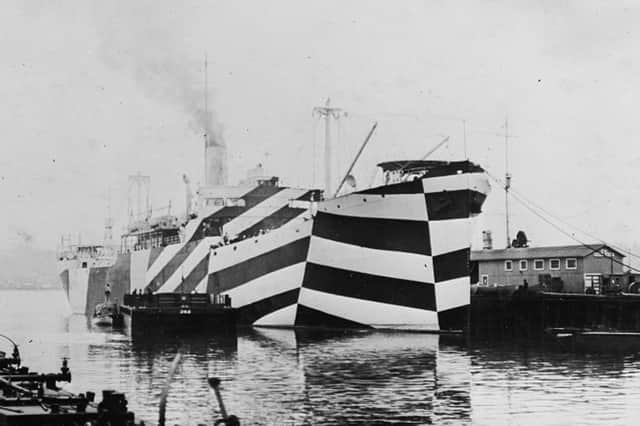

Wilkinson’s brainchild was dazzling in every sense – disruptive camouflage, using a simple form of graffiti on a grand scale to break up a ship’s shape.

The Admiralty soon grasped the advantages of Dazzle and Wilkinson was given command of a naval camouflage unit of 24 fellow artists in the basement of the Royal Academy, where in later years he would see his works admired in the galleries above.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said they first applied Dazzle to models, which were sent to the dockyards where the bold shapes and violent contrasts were painted to ships’ sides and superstructure. He was seconded to the USA in 1918 to help set up a comparable unit.

Dazzle painting gradually became obsolete in the Second World War, outmoded by radar and technology, and Wilkinson was then called on by the RAF to help camouflage airfields.

He spent much of the war sketching and recording the work of the Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and Coastal Command and the 52 dramatic paintings that resulted were exhibited as The War at Sea at the National Gallery.

Pablo Picasso claimed it was the Cubists who invented Dazzle, but the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors firmly established it was Wilkinson’s invention in time of necessity that got there first and awarded him £2,000.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe died in 1971 aged 92, but apart from his works which are on permanent exhibition, you need go no further than Portsmouth Historic Dockyard to see one of his most poignant contributions.

He served in the Dardenelles about the time that monitor HMS M33, one of a fleet of gunships ordered by Winston Churchill for inshore bombardment during the Gallipoli landings, was in action.

M33, one of only two surviving First World War warships, now sits resplendent with her fully restored Dazzle paint in No1 Dock – a fitting tribute to the man who went to war armed with paint box and palette.