'˜Japanese treated their own as they did their prisoners...'

Ninety-eight-year-old Bill Marshall, of London Road, Waterlooville, is one of them.

Born in Shrewsbury, he was an apprentice when war broke out and in the first week he volunteered and joined the RAF. He thought he might see action at home or perhaps in Europe, but what happened was beyond his worst nightmare.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeing promoted to an AC1 at Christmas 1940, Bill’s unit was posted to Singapore and then on to Sungei Patani to the north of Malaya. His team’s job was to provide oxygen for pilots flying at high altitude.

When the Japanese invaded Malaya, Bill’s base was badly bombed and he soon learned that exploding oxygen bottles could cause more damage than any bomb. Three-feet-square fragments were found half-a-mile away.

Bill and his pals managed to make their way to Singapore in a Dodge truck they had found abandoned.

But when the Japanese took Singapore they escaped on a convoy of five or six ships to Java. But there they were surrounded by the enemy who announced they would commit atrocities to the women if they did not surrender. There was no choice but to give up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe British troops were held in awful conditions in a former civilian jail infested with lice and bugs. They were put to punishing work with a measly food allowance and disease was rife. They were put to work filling in bomb-damaged airstrips.

At the end of 1942 the prisoners were herded on to ships and put into the holds of what became known as ‘hell ships’. They sat shoulder to shoulder with their knees tucked into their chests, packed together like sardines.

Bill says: ‘Many died on the voyage. They were boxed up and thrown unceremoniously into the sea.’ Their sacrifice did Bill, and the others who survived, a favour because more room became available.

During this voyage the ship passed through a typhoon and with many being sick and suffering from dysentery, conditions became intolerable. But somehow Bill managed to survive.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom the heat of the equator the ship arrived at the northern tip of Japan in freezing temperatures, at the island of Hokkaido, where they were given Japanese uniforms to wear – tropical kit, ragged through use, and not fit for purpose.

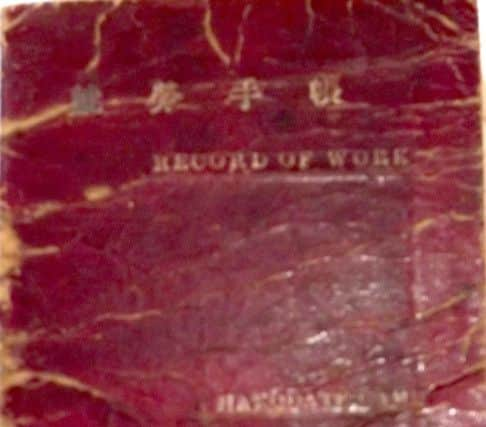

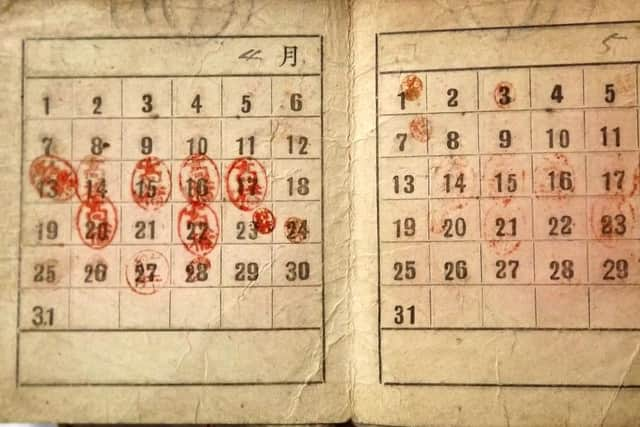

He and his fellow prisoners were put to work in an iron ore mine and although escape was impossible they saw it as their patriotic duty to cause confusion if possible. They kept productivity low and stole the guards’ rice and cabbage.

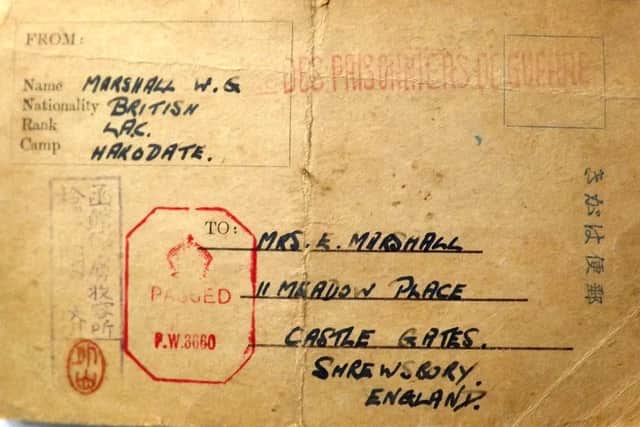

They were allowed to send home cards from time to time. On one, Bill wrote to his mother: ‘Just a few lines to let you know I am still in the running.’ On another: ‘I am unwounded and moderately happy. The time passes very quickly.’

But throughout his time as a prisoner, not once did he think he would not make it home. As long as he could keep himself together and as fit as possible, he knew there was a chance of seeing his parents again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of the conditions the men endured defy description. One was solitary confinement – being thrown into a pit dug by Bill and his comrades.

Bill says they were paid by the Japanese – a meagre sum which enabled him to buy cigarettes. ‘Lousy they were, but at least it was a smoke,’ he recalls.

‘The Japanese were a very strange, feudal nation and very cruel at that time. They appeared to treat their own people as they treated us. The officers beat the NCOs, they beat ordinary soldiers and they beat us. We were on the tail end of it all.’

For thousands of prisoners the horrendous conditions and lack of food proved too much and at least a third never returned home again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBill says: ‘Being a short, light bloke I didn’t need as much food as the bigger men and perhaps that is what kept me going.’

Eventually, the atom bombs were dropped.

‘When America dropped those two bombs, they saved my life. If the Americans had invaded Japan, the Japanese were going to execute all prisoners-of-war, but after Hiroshima and Nagasaki they gave in literally overnight.’

He says the Japanese seemed to vanish immediately and an American officer in the camp took over before, finally, the Americans arrived and Bill and his fellow men made their way to Nagasaki.

‘I could not believe it. Fifteen miles of the city were just flat waste ground. It had to be done of course, but at what cost to the Japanese...?’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBill then started on the long road home via San Francisco; a train to Halifax, Nova Scotia, then on board the Queen Elizabeth to England.

It was a three-month journey.

Seventy-one years on and, although the memories will never disappear, he bears no hatred for a nation that imprisoned him for more than three years. But there are some things he could never bring himself to do. ‘I’ll never buy a Japanese car!’ he says.

Bill Marshall will be 99 on November 21.

LIFE AFTER THE WAR

After the Second World War, Bill Marshall returned to civilian life and became an engineer. How one does that after such an horrendous three years I shall never be able to understand.

By 1970 he was working in the London office of John Brown Engineering as a planning engineer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe arrived in the company’s Portsmouth office to be head of project control engineering where he remained until retirement. He stayed on until the age of 70 as a consultant.

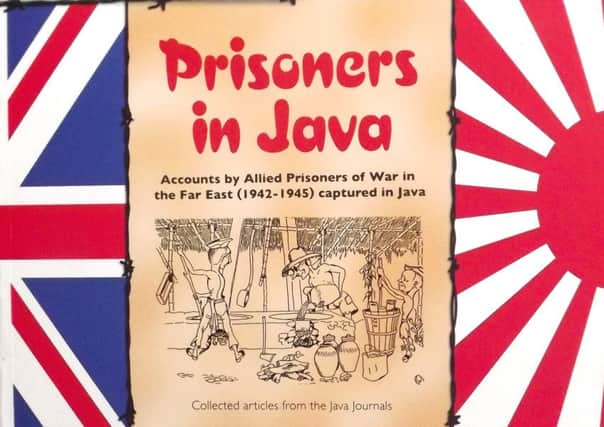

In 1983, 16 men started the Java Ex-Prisoners-of-War Club. Their aim was to look after fellow former PoWs and their pensions and to tell the world about the forgotten men of the Far East.

It is now administered by two women, both daughters of ex-members of the club. It grew to 300 members worldwide and with a grant from the National Lottery they have published an excellent book Prisoners of Java which is available from Bill. Just phone (023) 9225 6557. It will be the best £20 you have ever spent.

Bill is now president of the club along with patrons Dame Vera Lynn and Sophie, Countess of Wessex and this year he was invited to a Royal Garden Party.

Although now a widower he has two sons and a daughter and three grandsons and four great-grandchildren.