Portsmouth scientists uncover the 100 million year mystery of this gigantic flying dinosaur's secret of flight

Palaeontologists from the University of Portsmouth have uncovered the secret of the gigantic creature’s ability to fly.

For years, scientists have only been able to guess at how flying azhdarchid pterosaurs managed to support their long, thin necks while taking off and flying with heavy prey animals in their mouths.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese flying dinosaurs had necks longer than those of giraffes, and also evolved to support massive heads that often measured longer than 1.5 metres.

New CT scans of intact remains of the prehistoric giants discovered in Morocco have now solved the mystery.

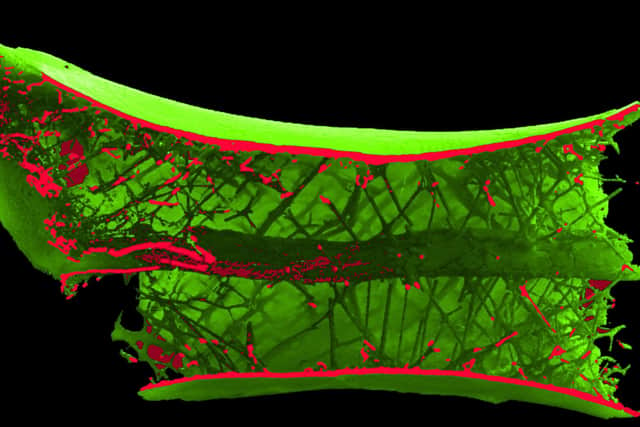

The scans reveal a complex image of spoke-like structures, arranged in a helix around a central tube inside the vertebra, similar to the spokes of a bicycle wheel.

This ‘lightweight’ construction offered strength without compromising the pterosaurs’ ability to fly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResearchers had originally set out to study the shape and movements of the neck, but took advantage of the offer of a CT scan to look inside.

Dave Martill, professor of palaeobiology at the university, said: ‘It is unlike anything seen previously in a vertebra of any animal.

‘The neural tube is placed centrally within the vertebra, and is connected to the external wall via a number of thin rod-like trabeculae, radially arranged like the spokes of a bicycle wheel, and helically arranged along the length of the vertebra.

‘They even cross-over like the spokes of a bicycle wheel.

‘Evolution shaped these creatures into awesome, breathtakingly efficient flyers.’