Strokes of genius

To reach it at the top of an old Methodist chapel you follow a labyrinthine series of corridors, mount several flights of stairs and you finally reach his aerie.

John, who had just arrived on his bicycle from his North End home, unlocks the door to what seems like an attic studio and reveals a room flooded with sunlight. Every inch of the walls is covered with his distinctive work.

And to complete the perfect image, it’s cold. Very cold.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it doesn’t matter, for this is John’s world – a world in which he is surrounded by the place which has inspired him to sketch and paint, Portsmouth Dockyard, where he worked for 40 years as a rigger, one of the toughest jobs.

There is a large easel on one side with a painting of a Dreadnought battleship from the First World War.

There’s a lovely silhouette of a dockyard worker with a seagull perched on his cap and then there are two caricatures, one of a rigger with an enormous length of rope slung over his shoulder, the other of a dockie holding what appears to be a steaming two-pint mug of tea.

Elsewhere there are images of destroyers, tugs, locks, basins and Dockyard characters who once represented the soul of Portsmouth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBrushes, palettes, crayons and an array of pens, pencils, inks and paper are scattered around his large desk and virtually every other surface in the room in the 31-studio Art Space Portsmouth which occupies that one-time chapel in Brougham Road, Southsea.

Now 74, John is a quietly-spoken, modest man – the sort who forgets he is wearing his cycle clips throughout the interview, but who burns with passion and pride about his talent.

He reaches across that large desk to a bookcase and pulls out a handful of dog-eared sketch books. Inside are sketches of Dockyard scenes, observations he made in lulls between jobs when the ’yard was in its pomp.

‘I always carried one in my pocket,’ he says, ‘just in case I saw something interesting.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe adds: ‘The Dockyard was such a wonderful place to capture, full of characters and marvellous pieces of engineering. I was lucky enough to work there when it was in its prime. It’s virtually all gone today.’

John was 15 when he went from St Luke’s School, Southsea, to be a yard boy in the Dockyard’s rigging section.

His dad was a welder there and he, like so many young men in the city, was destined to carry on the family tradition.

As he began his apprenticeship, an artistic flair first discovered in the classroom at Omega Street Junior School, Somers Town, was initially forgotten.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut 60 years later John now combines the two – sketching and painting scenes of Dockyard life from the time when it dominated the city.

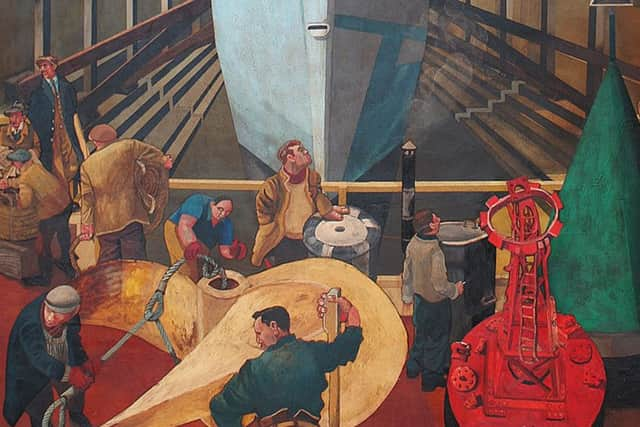

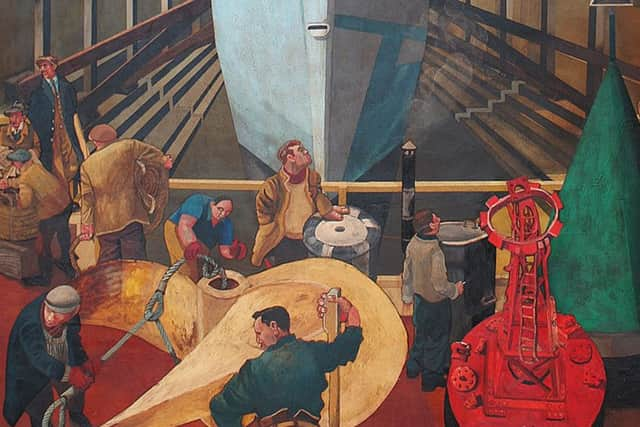

His images recall the glory days of 20,000 men working in the Dockyard, with the huge phalanx of cyclists pouring through the gate at out-muster time, a sight to behold.

After taking early retirement from the rigging section in 1996 – 40 years after he started work there – John studied for an art diploma at Southampton Institute. It is so good that some of his work has been sold in London galleries and now, from January 29, he is getting his first one-man show at Jack House Gallery in High Street, Old Portsmouth, with a second promised later this year.

John recalls the first time one of his pictures attracted praise. He was eight or nine and his Omega Street headmaster interrupted an art class and took a look at what he was drawing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘It was of some chickens we kept in the back yard at home in Lancaster Street off Somers Road. The headmaster said: ‘‘John, this is wonderful’’. I’ve never forgotten those words.’

Even though he had a natural talent, John was the oldest of three children growing up in that Somers Town home and he needed to start earning.

He adds: ‘I was good at drawing at school, but my dad said the best thing for me was to go into the Dockyard. It suited me because I was a footballer [he played for Waterlooville] and I got Saturdays off.’

Life as a rigger’s mate could be hard – they were often weighed down with the tools of the trade they had to carry to ships wherever they were berthed in the ’yard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn says: ‘The boys were all sizes, but the small ones would have massive heaving lines wrapped around them that were as big as they were.’

Apprentices also had to know their place. ‘As a boy I had to go to see the master rigger who was a naval commander. He told me: ‘‘Eyes open, mouth shut. You remember that and you’ll be OK.’’

‘Some of the men seemed like giants. A lot had come back from the war and didn’t want a little whippersnapper back-chatting them.’

He remembers working on battleships such as HMS Vanguard and HMS Victory. Riggers had to climb masts and pull ships alongside and across basins using capstan wires and hawsers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn says of the 1950s and 1960s: ‘In those days everything was done by manpower. They were wonderful times.

‘I’d get my sketch book out at every spare opportunity and eventually I gained a reputation in the Dockyard as ‘‘the dockie who draws’’.’