The dramatic day Vanguard came close to disaster

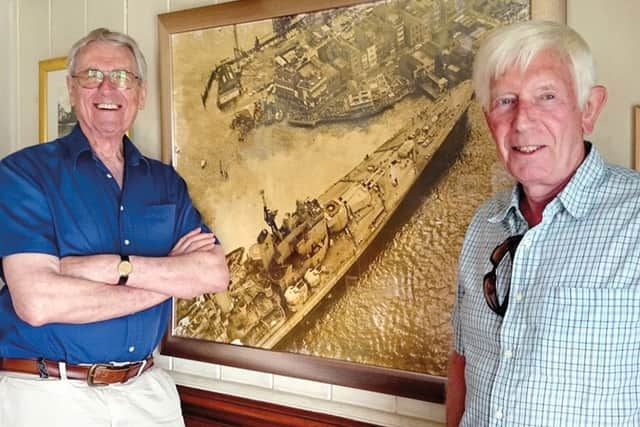

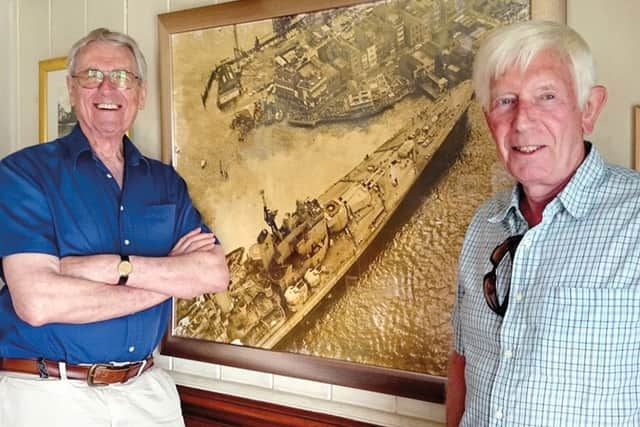

Evening News chief photographer Roy West and the paper’s naval correspondent Tim King were covering Vanguard’s departure to the breaker’s yard from the air and from on board the ship.

But what started as a nice day out of the office suddenly became one of the most dramatic post-war news stories.

Tim King’s story

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy task was to write a colour piece for the next day’s paper and I was ferried out to Vanguard in a dockyard tug to where she’d been moored in the upper harbour for the past four years.

I watched from 50ft up on the bridge as the dockyard tugs gingerly manoeuvred Vanguard’s massive bulk through to point her towards the harbour entrance, and the tow began with two tugs pulling ahead at about four knots, with one moored on each side amidships and two others astern.

It was a fine, warm day and I had all the time in the world to soak up the nostalgia for my story.

Then it all went from shipshape to pearshape.

As we passed Middle Slip Jetty, the bows began to swing relentlessly to port. By the time we passed South Railway Jetty, Vanguard’s immediate fate was sealed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe two tugs towing ahead – Antic and Capable – churned across to the starboard side with hawsers straining to correct the drift, while the others were revving full astern in a vain bid to haul the bows away from where they were now headed – the Still and West and hundreds of sightseers crowding Point.

The skeleton crew shouted and gesticulated to get clear, but the crowd – mostly holidaymakers – thought it was Jolly Jack bringing the relic closer to their Brownies. They waved back.

Only split-second timing by Portsmouth senior pilot Roy Ottley prevented inevitable carnage and as I stood beside him on the rusting bridge, he gauged the precise moment and ordered: ‘Let go starboard anchor.’

The hero of the hour told me later he suddenly remembered chains that guided the old floating bridge between Point and Gosport were still there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe anchor flukes, which normally dig into the seabed, caught the chains which held and at the last second dragged the bows away from the sea wall and the waving crowds only yards away.

As Vanguard grounded at 10.35am in 24ft of water, she pointed at the nearby Customs Jetty where a coaster was berthed. I’ve never seen a crew move so fast to slip mooring ropes and save their ship. One disaster had been avoided, now another was imminent.

Vanguard drew 28ft for’ard and the dockyard tugs were not powerful enough to move her. The tide was ebbing, the stern began swinging outwards and the situation was desperate.

Had the two ocean-going tugs Samsonia and Bustler that were to take Vanguard to her graveyard not arrived, she would have swung broadside across the harbour entrance and broken her back at low tide, effectively blockading the premier naval port for months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe bigger tugs saved the day and the battleship that had briefly scorned her executioners was hauled clear at 11.15 with only minutes to spare.

As the drama unfolded, I realised I then had a duty to write something for that day – not easy before modern technology such as WiFi and mobile phones were invented.

Vanguard had been stripped and I was captive in a dead ship with no shore communication. Journalists of my era were taught to think on their feet and use initiative, so I went into the pitch-black wireless cabin, found an old naval signal pad and some wire and ripped out a weighty brass plug.

Using an ammunition locker as a desk, I scribbled out 17 paragraphs, wrapped my copy round the plug with the wire, went to the starboard bow and lobbed it down to a colleague who’d come alongside in a Press boat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLuckily, he caught it and my story made it into the next editions. Thus ended the era of naval might that depended on slugging it out broadside to broadside and my last sight of the Royal Navy’s largest, most powerful and most beautifully-designed battleship, which never fired a shot in anger, was her awesome silhouette disappearing to the horizon and her fate at Gare Loch in Scotland.

Roy West’s story

‘We took off in an Auster single-engine plane from Portsmouth Airport. The pilot, Ian Mitchell, first circled around Lee Tower because we were not sure whether other aircraft were around over the harbour.

‘The door had been taken off my side to give a clear view and to avoid camera vibration. I was just strapped in with a lap belt, holding my camera with a leather bag between my feet containing the glass camera plates.’ As they circled, Ian laughed and said: ‘Wouldn’t it be great if she went aground!’ Roy retorted: “Some hope of that...”

Hardly had the words come from Ian Mitchell’s mouth when his wish for the seemingly impossible started unfolding hundreds of feet below.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘We noticed an extraordinary amount of foam surrounding the ship. We knew then something was wrong and Ian automatically went down for a closer look.’

What they saw was the incredible sight of 42,000 tons of armour slipping gradually, almost majestically out of control as Vanguard’s funeral procession was plunged into disarray, but by that time the battleship was heading seemingly unstoppable for the Still and West and disaster.

As Vanguard grounded, Roy got a splendid shot of the entire 814ft long warship. Then the pilot, sensing there was more in the offing, swooped lower and, with his last but one plate, he captured THE close-up picture that won national acclaim.

‘We didn’t have light meters at that time, but used our experience and I remember clearly that I took it at 1,000th of a second at F8,’ said Roy, now retired and living in Old Portsmouth, a stone’s throw from where the drama was played out.