STEVE CANAVAN:A rather depressing anniversary

Thankfully the jet landed safely – which I suppose shows how robust and safe they actually are – but the thought of being 30,000 feet in the air with a knackered engine is as high on my bucket-list as running a marathon in high heels while carrying an elephant on my back.

The incident reminded me, however (and apologies for bringing the mood down here), that today marks a rather depressing anniversary – the first time a human died in an air crash.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

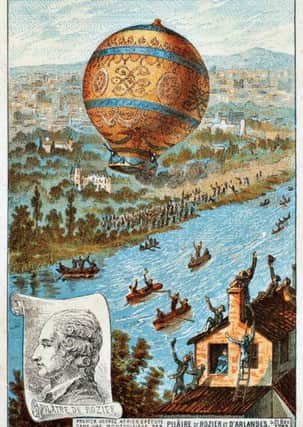

Hide AdThe dubious honour belongs to grandly-named Frenchman Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, who perished on this day in 1785 when the balloon he had invented fell from the sky – at which point I imagine he must have been kicking himself that he’d not taken a bit more care at the design stage.

I know this, by the way, not because I’m some weirdo with a fetish for strange facts (though that actually does happen to be true) but because I recently read a book about air travel.

That’s right; some people get their kicks from drugs, sex or gambling – I get mine from reading non-fiction literature about aviation.

I remember the chapter about Rozier because he was one of those slightly bonkers inventors, the type who would go to extraordinary lengths to find things out.

There seemed to be a lot of those folk in years gone by.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNewton, for example – apple on the head gravity bloke, not the former Chelsea midfielder Eddie – stuck needles in his own eyes while studying optics ‘to see what would happen’. What happened was that it bloody hurt and he had trouble reading the paper that night.

Then there was 25-year-old German surgical trainee Werner Forssmann, who drilled a hole in his arm and using two feet of cable, pushed a catheter all the way up his limb and into his heart, all in the name of medical science.

He expected gratitude but was instead fired by his employers ‘for not gaining permission’ for his experiment ... though he had the last laugh, winning the 1956 Nobel Prize for Medicine for developing a procedure that allowed for cardiac catheterization. Ironically, Forssmann later died of heart failure.

Anyhow, back to our hot air balloon man Rozier, who was similarly eccentric with his experiments, testing the flammability of hydrogen by gulping a mouthful and then blowing across an open flame – proving at a stroke, as author Bill Bryson put it, ‘that hydrogen is indeed explosively combustible and that eyebrows are not necessarily a permanent feature of one’s face’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRozier’s expertise was in physics and chemistry but after witnessing the first public demonstration of a new-fangled invention called the hot air balloon, he became fixated.

It was obviously a bit dangerous back then – the balloons were primitive to say the least – so for the first ever manned flight, the King of France (Louis XVI) decided it should contain two condemned criminals (now that’s what you call day release).

Rozier, though, argued the honour of becoming the first balloonists should belong to someone of a higher status and so volunteered himself.

He and a friend rose 3,000 feet and travelled five miles in 25 minutes before landing to huge acclaim.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlas, after a few more flights on balloons designed by others, Rozier decided to build his own, with the aim of becoming the first man to cross the English Channel.

Two things went wrong. First, someone else beat him to it, and, secondly, when he did eventually make his attempt, in June 1785, the wind changed direction, his balloon suddenly deflated and a presumably really cheesed-off Rozier plunged 1,500 feet to his death.

He does, as a result, have the eternal honour of becoming air travel’s first fatality, though whether that was much comfort at the time is open to debate.